The Origins of Shitō-Ryū

The most widely practiced of

the late-19th century styles of karate was called

Shuri-te ("karate from

Shuri"). Shuri was the capital of Okinawa and the

Ryūkyū Islands. Shuri-te was

a system of unarmed combat developed by the warriors and royal bodyguards who

protected Shuri Castle and the royal family, so it was designed for situations in which the practitioner

was either forbidden to have a weapon (such as inside

the castle), or had been disarmed during battle.

Therefore, the majority of Shuri-te techniques are

designed and intended to defend against an armed

opponent who is attempting to invade a castle and/or

assassinate its occupants. And since Okinawa had been conquered by

the Satsuma Han of Kyūshū in 1609 and controlled

thereafter by a Japanese occupation force, the weapons

Shuri-te was designed to defend against were the typical arms of the samurai,

primarily swords, spears, jutte, and staves -

often in cramped spaces.

For this reason, Shuri-te emphasises remaining out of

range of these weapons until an opportunity is created

to lunge quickly in with a single, devasting

counter-attack. During Mabuni Kenwa's youth, the

premier teacher of Shuri-te was Itosu Ankō

(1831-1915), who served as personal bodyguard to the

last independant king of the Ryūkyū Islands.

The most widely practiced of

the late-19th century styles of karate was called

Shuri-te ("karate from

Shuri"). Shuri was the capital of Okinawa and the

Ryūkyū Islands. Shuri-te was

a system of unarmed combat developed by the warriors and royal bodyguards who

protected Shuri Castle and the royal family, so it was designed for situations in which the practitioner

was either forbidden to have a weapon (such as inside

the castle), or had been disarmed during battle.

Therefore, the majority of Shuri-te techniques are

designed and intended to defend against an armed

opponent who is attempting to invade a castle and/or

assassinate its occupants. And since Okinawa had been conquered by

the Satsuma Han of Kyūshū in 1609 and controlled

thereafter by a Japanese occupation force, the weapons

Shuri-te was designed to defend against were the typical arms of the samurai,

primarily swords, spears, jutte, and staves -

often in cramped spaces.

For this reason, Shuri-te emphasises remaining out of

range of these weapons until an opportunity is created

to lunge quickly in with a single, devasting

counter-attack. During Mabuni Kenwa's youth, the

premier teacher of Shuri-te was Itosu Ankō

(1831-1915), who served as personal bodyguard to the

last independant king of the Ryūkyū Islands.

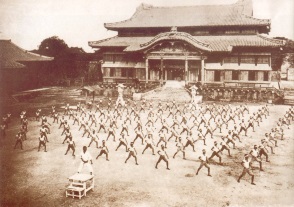

Around the time of the first recorded masters of karate, one of the busiest seaports in the world was the Okinawan city of Naha. For centuries, it was a major center of trade for the nations in the Far East, its harbour filled with ships and its docks cluttered with trade goods. It was a primary target of opportunity for pirates and thieves, so contingents of highly skilled and experienced guards for the merchants and their wares arrived aboard the vessels docking in Naha. And when their duties were complete, these guards frequented the taverns, restaurants, and brothels of Naha to relax and occasionally let off steam. As a result, Naha-te ("karate from Naha") was a blend of Chinese, Japanese, Indo-Chinese, and native Okinawan fighting skills. During Mabuni Kenwa's youth, the leading proponents of Naha-te were Aragaki Seishō (1840-1918) and his primary student, Higaonna Kanryō (1853-1915).

The other significant Okinawan town of that time was Tomari. Tomari was a beach town that served as a secondary port, exclusively for inter-island trade within the Ryūkyū kingdom. It was also a fishing village and, because it attracted trade from other islands, it was a marketplace for many local farmers and tradesmen. Since trade in Tomari was primarily between peasants, there were fewer highly-trained warriors roaming Tomari than in either Naha and Shuri, so Tomari-te ("karate from Tomari") tends to be cruder than Shuri-te, while including techniques found in both Shuri-te and Naha-te, and features techniques adapted to fighting in mud or wet sand. The last to practice Tomari-te exclusively were Matsumora Kōsaku (1829-1898) and Oyadomari Kōkan (1827-1905), and the style effectively died with them at the dawn of the 20th century. Fortunately, Kyan Chōtoku (1870-1945), and Motobu Chōki (1870-1944) learned several Tomari-te kata from them, which Mabuni Kenwa in turn learned from them and preserved as part of his Shitō-ryū system.

In 1902, a sickly 13-year-old boy named Mabuni Kenwa was introduced to Shuri-te master, Itosu Anko in hopes that rigourous training in karate would strengthen both his body and spirit. It was an introduction of true historic significance!