Shinsei Description

After bowing and announcing the name of the kata ("Shinsei") ...

Yōi (cross open hands at groin level in

musubi dachi) and kiyomeri kokyū

(purification breaths)

Kamaete (shift both feet simultaneouslyinto nami heikō dachi

while closing hands into fists at hip—not knee—width)

| 1 | Turn (Naha-te method) 90 degrees left into hidari sanchin dachi with hidari age uke | |

| 2 | Step forward into migi han-zenkutsu dachi with migi oizuki | |

| 3 | Step back with right foot into hidari kōkutsu dachi with hidari gedan barai | |

| 4 | Turn (Naha-te method) 90 degrees right into migi sanchin dachi with migi age uke | |

| 5 | Step forward into hidari han-zenkutsu dachi with hidari oizuki | |

| 6 | Step back with left foot into migi kōkutsu dachi with migi gedan barai | |

| 7 | Step forward into hidari sanchin dachi with hidari kakete uke | |

| 8 | Right foot choku geri, landing forward in migi shikō dachi with migi agezuki, followed immediately with migi uraken uchi, migi gedan barai, and hidari kagi zuki with kiai | |

| 9 | Turn (Naha-te method) 90 degrees left into hidari sanchin dachi with hidari kakete uke | |

| 10 | Step forward into migi sanchin dachi with migi kakete uke | |

| 11 | Left foot choku geri, landing forward in hidari shikō dachi with hidari agezuki, followed immediately with hidari uraken uchi, hidari gedan barai, and migi kagi zuki with kiai | |

| 12 | Turn (Shuri-te method) 180 degree right into migi neko-ashi dachi with migi yoko ura-shutō uke | |

| 13 | Step back with right foot into hidari neko-ashi dachi while sweeping left hand across the front of the body in haitō uchi to the right hip | |

| 14 | In place mawari uke (ude-karami nage) |

.......... NOTE: zanshin yame is NOT

performed in Shinsei

Naotte (perform tekagami movement while

drawing left foot back into musubi dachi)

Rei (bow)

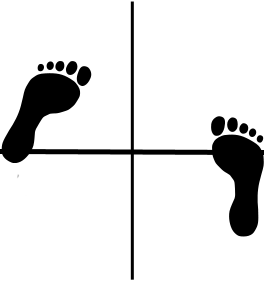

As

shown in the diagram at left, sanchin dachi is shoulder

width from heel to heel, with the heel of the leading

foot (left foot in the diagram) aligned with the ball of

the trailing foot (right foot in the diagram). The

outside edge (sokutō) of the trailing foot is

parallel to the direction of the stance, as in heikō

dachi, but the sokutō of the leading foot is angled

inwards about 30 degrees. Your body weight should

be centered between the feet, both side-to-side and

front-to-back, as indicated by the intersection point

(+) of the vertical and horizontal centre-lines in the

diagram. Ankles, knee, and hips should all be bent

so that your height is the same as in han-zenkutsu

dachi, but the back and neck must remain straight; not

bent or hunched forward.

As

shown in the diagram at left, sanchin dachi is shoulder

width from heel to heel, with the heel of the leading

foot (left foot in the diagram) aligned with the ball of

the trailing foot (right foot in the diagram). The

outside edge (sokutō) of the trailing foot is

parallel to the direction of the stance, as in heikō

dachi, but the sokutō of the leading foot is angled

inwards about 30 degrees. Your body weight should

be centered between the feet, both side-to-side and

front-to-back, as indicated by the intersection point

(+) of the vertical and horizontal centre-lines in the

diagram. Ankles, knee, and hips should all be bent

so that your height is the same as in han-zenkutsu

dachi, but the back and neck must remain straight; not

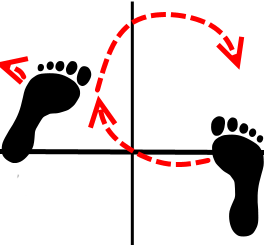

bent or hunched forward. When moving in sanchin dachi, the

active foot slides across the floor in an elliptical

pattern, as depicted in the diagram at right, its path

nearly grazing the stationary foot as it passes, then

sweeping forward to a point well beyond its final

position before circling back to its ending point less

than a single foot-length ahead of its starting

position. The stationary foot simply pivots outward on

the heel until its sokutō (outer edge) is

parallel to the direction of the stance.

When moving in sanchin dachi, the

active foot slides across the floor in an elliptical

pattern, as depicted in the diagram at right, its path

nearly grazing the stationary foot as it passes, then

sweeping forward to a point well beyond its final

position before circling back to its ending point less

than a single foot-length ahead of its starting

position. The stationary foot simply pivots outward on

the heel until its sokutō (outer edge) is

parallel to the direction of the stance. When

learning any new kata, it is important to remind

oneself of the adage: "Manabu no tame ni hyakkkai,

jukuren no tame ni senkai, satori no tame ni manga

okonau" (学ぶのために百回、熟練のために千回、悟りのために万回行う.).

A hundred times to learn, a thousand

times for proficiency, ten thousand

repetitions for complete understanding.

A related Okinawan saying is "ichi kata san nen"

(一型三年): one kata three years. Think

of it this way: it takes about 40 seconds to

perform Shinsei. So in just ten

minutes per day for only ten days (or twenty minutes a

day for just five days), you can learn the correct

sequences of movements in Shinsei.

But to become truly proficient-to be able to perform it

correctly, and with the speed, power, timing, and bushi damashii (samurai spirit) necessary

to make its techniques effective in a real self-defence

situation will take a thousand repetitions, which

equates to 100 days at ten repetitions a day.

And to fully understand and apply all of its principles,

nuances, and variations will take 1,000 days (three

years) at ten repetitions per day.

When

learning any new kata, it is important to remind

oneself of the adage: "Manabu no tame ni hyakkkai,

jukuren no tame ni senkai, satori no tame ni manga

okonau" (学ぶのために百回、熟練のために千回、悟りのために万回行う.).

A hundred times to learn, a thousand

times for proficiency, ten thousand

repetitions for complete understanding.

A related Okinawan saying is "ichi kata san nen"

(一型三年): one kata three years. Think

of it this way: it takes about 40 seconds to

perform Shinsei. So in just ten

minutes per day for only ten days (or twenty minutes a

day for just five days), you can learn the correct

sequences of movements in Shinsei.

But to become truly proficient-to be able to perform it

correctly, and with the speed, power, timing, and bushi damashii (samurai spirit) necessary

to make its techniques effective in a real self-defence

situation will take a thousand repetitions, which

equates to 100 days at ten repetitions a day.

And to fully understand and apply all of its principles,

nuances, and variations will take 1,000 days (three

years) at ten repetitions per day.